In the world of data extraction, efficiency and reliability are everything. When you’re running a suite of scrapers—each with its own demands—you quickly realize that traditional infrastructure can become a major bottleneck. I recently faced this challenge firsthand with a project that involved running around 30 different scrapers for e-commerce sites like Amazon, Walmart, and eBay.

The Problem with a Single VM Link to heading

Initially, all of these scrapers ran on a single, powerful VM (an t3.2xlarge instance with 8 vCPUs and 32GB of memory). This setup seemed sufficient at first, but it quickly ran into two major issues.

First, resource contention. Running multiple memory-intensive bots on a single machine led to frequent crashes and out-of-memory errors. The VM simply couldn’t handle the load, especially when I needed to run multiple scrapers at once, several times a day.

Second, we were limited by the frequency of execution. We couldn’t scale our operations without a significant hardware upgrade, which would have meant more cost and more management overhead. I knew there had to be a more efficient way to handle this, one that didn’t require me to constantly manage a server.

My solution was to move to a serverless architecture that would allow me to run scrapers on-demand, without the hassle of managing VMs or worrying about resources.

The Serverless Solution: AWS Step Functions, Lambda, and Fargate Link to heading

I chose a combination of AWS Step Functions, Lambda, and ECS Fargate to build a robust and scalable solution.

- Lambda was perfect for our HTTP-based scrapers. We packaged each one in a containerized image and deployed it to Lambda. This allowed us to run them quickly and on-demand.

- ECS Fargate was reserved for more demanding tasks. These were the browser-based bots that used tools like Selenium, which are memory-intensive and often take longer than Lambda’s 15-minute timeout limit. Fargate provided a managed, serverless compute environment for these tasks.

- Step Functions became the heart of the system. I used it to orchestrate the entire process, manage parallel executions, and increase concurrency across all our scraping workflows.

A Look at the Workflows Link to heading

To better illustrate this, let’s break down two of the primary workflows we created.

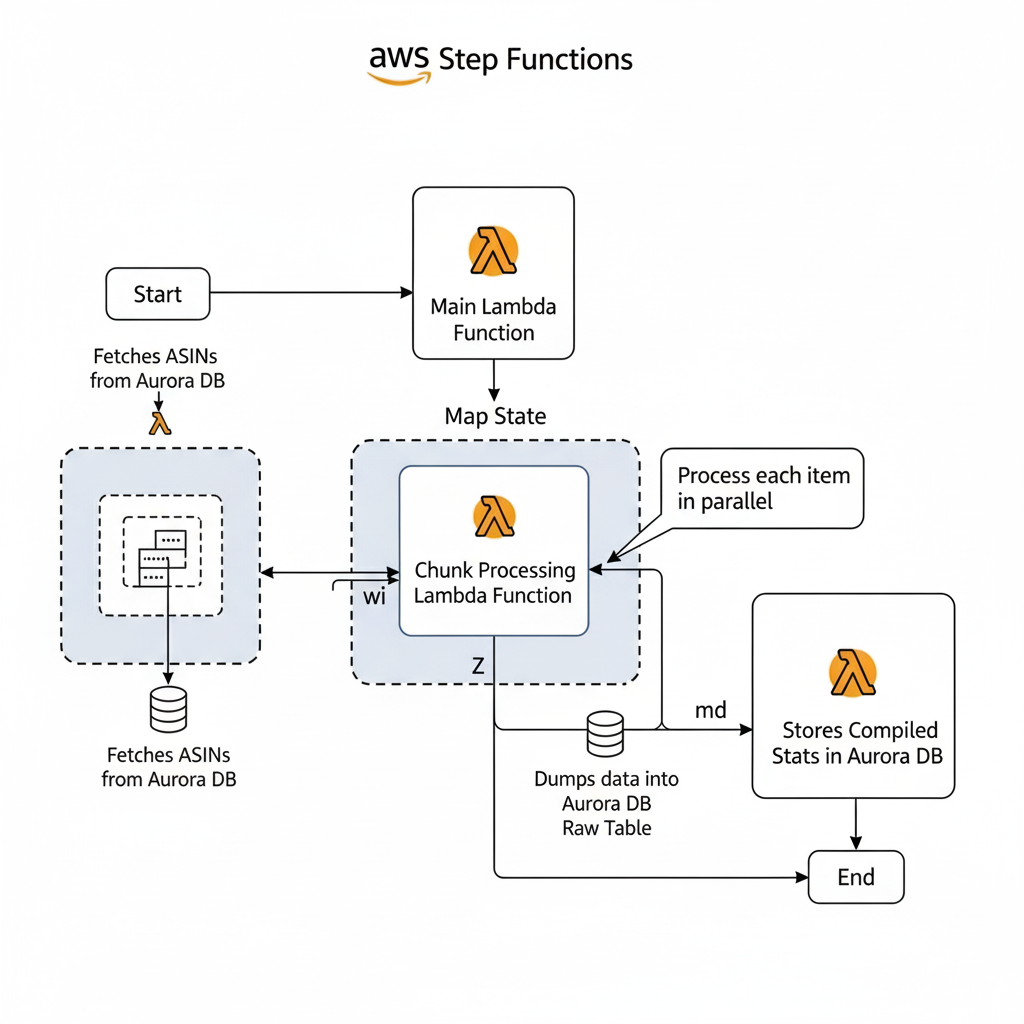

Step Functions-Lambda Workflow Link to heading

For one of our key projects, we needed to scrape offers for a large list of Amazon ASINs (Amazon Standard Identification Numbers). Here’s how the workflow was designed:

- Main Lambda Function: A primary Lambda function first fetched all the ASINs from an Aurora DB. It then divided them into manageable chunks to be processed in parallel.

- Map Workflow State: I used a Map Workflow State to invoke a separate Lambda function for each chunk. This allowed us to run many instances simultaneously. Each Lambda instance was responsible for scraping its assigned chunk of ASINs.

- Data Handling: Once a Lambda finished, it would dump the scraped data into a raw table in the Aurora DB and return its execution statistics.

- Closing Lambda Function: After all the parallel Lambda executions were complete, a final Lambda function was triggered. Its job was to collect all the execution stats, compile them into a summary, and store them in the database for analysis.

This model was repeated for many other sites that relied on straightforward HTTP scraping.

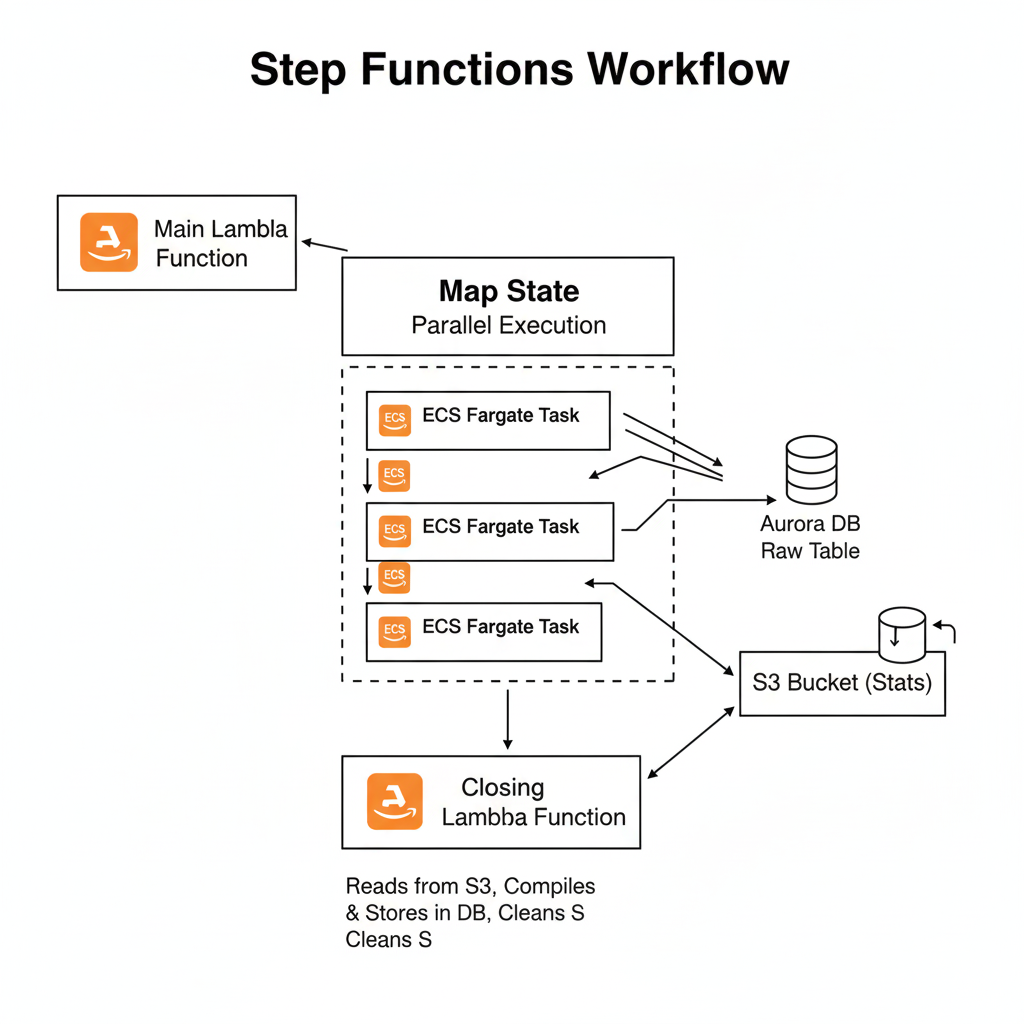

Step Functions-ECS Fargate Workflow Link to heading

For the more resource-intensive, browser-based scraping, we used a similar approach but replaced Lambda with ECS Fargate tasks.

- Main Lambda Function: Just like before, a Lambda function fetched the data from the DB and broke it into chunks.

- Map Workflow State: This time, a Map Workflow State was used to launch an ECS Fargate task for each chunk.

- Data Handling: Once a Fargate container finished, it wrote its data directly to a raw table in the Aurora DB. Since tasks running on Fargate can’t return a payload to Step Functions, we wrote the execution stats to an Amazon S3 bucket.

- Closing Lambda Function: The final Lambda function collected all the execution stats from the S3 bucket, compiled them, stored them in the database, and then cleaned up the S3 bucket by removing the temporary files.

Key Learnings and Constraints Link to heading

While the architecture was highly successful, there were a few key limitations we had to work around:

- Lambda Timeouts: We had to carefully set the chunk size to ensure our Lambda functions would complete their work before hitting the 15-minute timeout limit. We also implemented appropriate timeouts for each HTTP request to prevent the entire function from failing on a single slow response.

- Concurrency Limits: Although a single Step Function can theoretically execute up to 1000 tasks at once, our tests showed a practical limit of around 40-45 parallel Lambda executions per single workflow.

Conclusion Link to heading

By migrating our scraping operations to a serverless architecture, we were able to achieve significant improvements. Our costs were reduced to a third of what we were paying for a dedicated VM, largely due to the pay-per-use model and the AWS Lambda free tier.

Most importantly, we gained true scalability and reliability. We can now run our scrapers on-demand without worrying about resource contention or manual management, freeing us up to focus on the data, not the infrastructure. This approach demonstrates a powerful way to leverage serverless services for common backend challenges.